Japanese architect Arata Isozaki has made his mark on the profession—both in the physical landscape and in the minds, theories, and ideas of his colleagues. In the 1960s and 1970s, hewas a leading member of the Japanese new-wave movement, an avant-garde conceptual approach to architecture—though he aims to defy characterization within any single school of architectural thought. He approaches each project on its own merits, its place, its purpose, and its time.

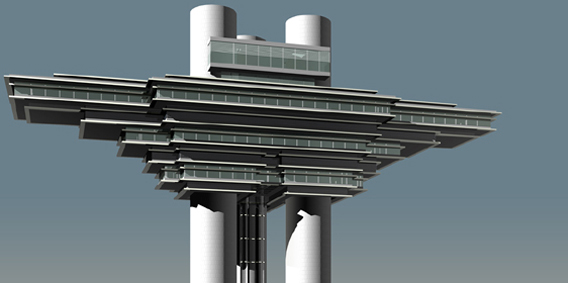

The architect recently completed a national convention center in Qatar (the QNCC). Opened in 2011, it has been called “one of the greenest convention centers in the world,” no small feat for one of the world’s leading emission-emitting countries. The complex was the first of its kind to receive LEED Gold certification. Its green roof, with 3,600 square meters of solar panels supplies 12.5 percent of the building’s projected energy needs; inside, LED lights and fixtures and zone-based air control systems reduce energy consumption.

The QNCC, designed in conjunction with RHWL Architects, is the largest convention center in the Middle East.It can hold thousands of visitors and spectators, and houses ten performance venues, a conference hall and theater that together hold more than six thousand, dozens of meeting rooms, multiple three-tiered auditoriums, and forty thousand square meters of exhibition space. It is in Education City, situated near elite universities and research and technology institutions, and twenty minutes from the area’s central business district. The complex serves as an addition to what one DesignBoom writer called “a new global hub of ideas and innovation.”

Isozaki graduated from the University of Tokyo in 1954, and then worked for Kenzo Tange & Urtec until 1963, when he established his own practice as a designer and theorist. For more than half a century, he has been thinking, writing, building, and influencing. Isozaki has taught at many universities around the world, his work has been exhibited widely, and it is clear his ability to mentor young architects has reached into the walls of his office. His past employees include award-winning international architects Shigeru Ban and Jun Aoki. He has also served as an architectural critic and as a jury member for major public and private architecture competitions. His website profile states, simply and confidently: “he has contributed significantly to making the visions of the world’s most radical architects a reality.” Others have recognized his role as well: his numerous awards include the prestigious RIBA Gold Medal, which he was awarded in 1986.

Isozaki has been no stranger to significant cultural projects in major cities. Some of his most renowned projects include Gumma Prefectural Museum of Modern Art in Japan (1971–74), Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (1981–86), Team Disney Building in Orlando, Florida (1989–90), Olympic Stadium’s Sports Hall in Barcelona (1992), Kyoto Concert Hall in Japan (1995), and Shenzhen Cultural Center in China (2005). Such works are known for their bold forms, unique details, and a combination of local and international influences. For instance, his Team Disney Building, which received an AIA National Honor Award, uses a Japanese yin-yang theory of positive and negative space. He incorporated a looped gateway that resembles Mickey Mouse’s ears, a hint of his often-ironic approach to architecture, and he built an ornamental sundial into the central cylinder—a reference to the time-conscious businesspeople who would use the space.

In addition to more than half a century of architectural work, Isozaki has designed exhibitions and stages, and has curated numerous international exhibitions, including three architectural exhibitions at the Venice Biennales. And in the 1980s, he experimented with product design, including a scarf for Louis Vuitton, jewelry for Cleto Munali, and other works. As Isozaki continues to resist following specific style guidelines, we can continue to expect award-winning works that relate to social and cultural needs, place, and time.