Boundaries—in design and in life—do not seem to be a concern of Zaha Hadid. The Baghdad-born British architect has been breaking them since before she stepped onto the international architecture scene, and continues to do so with each new idea, from her dynamic sketch-paintings and earliest built works to her upcoming Miami skyscraper.

She is known as forceful and uninterested in compromise; sticking to her convictions has caused her to earn the label “diva” in her male-dominated profession. But she is not intimidated, and is unafraid to fight back on such criticisms: when her Cincinnati Art Center building opened in 2003, her staff wore T-shirts that read: “Would they call me a diva if I were a guy?”

Hadid enrolled in London’s Architectural Association (AA) in 1972 after already having received a mathematics degree (another male-dominated field) from the American University in Beirut. At the AA, she was part of a new group of modernist designers. Unlike the clean, rational lines of their early twentieth-century predecessors, these modernists deconstructed a building’s geometry and then put it back together in new, dynamic ways.

After completing her degree in 1977, she immediately went to work as a partner at fellow architect Rem Koolhaas’s young Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA). But in 1980, she founded her own eponymous practice and there, she followed her own vision, whether anyone else liked it or not.

For much of her early career, Hadid did not build: her designs were too dynamic, too original, and scared off developers, but she would not waver or compromise to create more approachable or ordinary designs. And her preliminary sketches are nothing to snicker at; they have taken on a life of their own. New York’s Museum of Modern Art first introduced her works on paper into its collection—specifically from her “Peak” series—in the early 1990s, and other major art institutions have since followed suit.

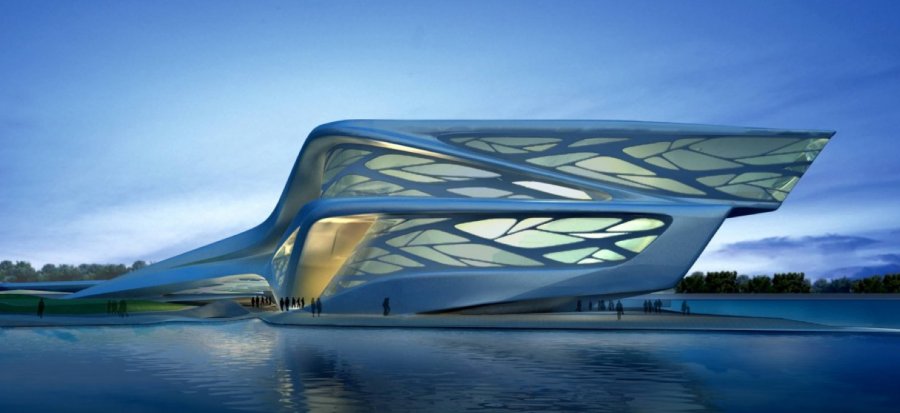

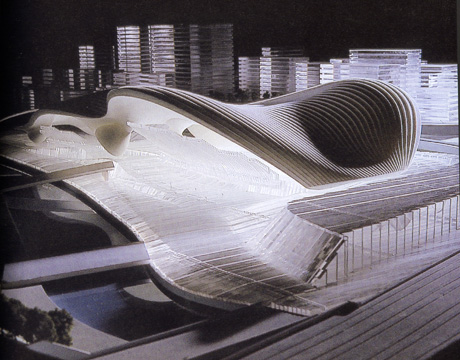

She looks to early twentieth-century Russian Suprematist and Constructivist painters, as well as traditional Chinese art and her travels through China for inspiration. In the “Peak” series, the buildings seem to float above a jagged topography—it is little wonder why she makes builders nervous. Although the paint is static, its sharp, confident, unexpected lines appear to move, something that would later be said of her buildings.

In 1993, she realized her first project: the Vitra Furniture Factory at an old fire station in Weil am Rhein, Germany. Her next major commission came with the Lois & Richard Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati, Ohio, completed in 2003. Hadid’s work has been called a “baroque modernism”—it shatters formal rules and viewpoints of the early twentieth-century modernists and reimagines space to seemingly transform before one’s eyes.

The year after the art center opened, her fate as an internationally influential architect was sealed: she received the Pritzker Architecture Prize—the profession’s highest honor—and was the first woman to do so in the award’s twenty-six-year history. Since then, her work in both two and three dimensions has been a staple in architectural and mainstream presses.

Most recently Hadid has been in the news for her commission to build a Miami high-rise residence along the waterfront. It is sited for the popular Biscayne Boulevard, where condo towers dominate. It will be the architect’s first skyscraper in the Western Hemisphere, and she was commissioned for the major building before even putting pencil to paper. The design is scheduled to be released early in 2013, and the press is eagerly awaiting the plans.

In addition to her Pritzker Prize, Hadid has received numerous other awards, including the Royal Institute of British Architects’ highest honor, the Stirling Prize, in 2010 and 2011, and she has been named Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) for her built work in the UK. But her name—and influence—reaches well beyond the architectural presses. Glamour magazine named Hadid Woman of the Year for 2012 and in 2010, she was honored as the UNESCO Artist for Peace and led Time magazine’s “Thinkers” category in its 100 Most Influential People in the World list.

In addition to her Pritzker Prize, Hadid has received numerous other awards, including the Royal Institute of British Architects’ highest honor, the Stirling Prize, in 2010 and 2011, and she has been named Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) for her built work in the UK. But her name—and influence—reaches well beyond the architectural presses. Glamour magazine named Hadid Woman of the Year for 2012 and in 2010, she was honored as the UNESCO Artist for Peace and led Time magazine’s “Thinkers” category in its 100 Most Influential People in the World list.

Not surprisingly, Hadid is known, and admired, for her theoretical and academic work as much as she is for her dynamic buildings. She has taught at the AA, Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, the University of Chicago School of Architecture, Columbia’s Masters Studio, Yale, and elsewhere. She has also had retrospective exhibitions at New York’s Guggenheim Museum (2006), London’s Design Museum (2007), and Italy’s Palazzo della Ragione (2009). According to Hadid’s website, her firm has worked on 950 projects in 44 countries and has a 350-person staff—no small numbers for a female architect whose work was once considered unbuildable.